My 2 x great grandfather William Taylor CLARK (1819-1902) was a harpooner on whaling ships sailing for most of his career out of Hull, and then later from Dundee. Sadly he left no personal recollections of his life, written or in the form of stories handed down.

His Seaman’s Ticket records that he was born 30 November 1819, that he was 5ft 6.75in tall, had black hair, brown eyes and a fresh complexion, a cut on his upper lip, and that he first went to see at the age of just eleven. Harpooners don’t seem to have ever had a good press, then or now. I’ll write a separate post at some point about the indefensibility of whaling, juxtaposed as it must be against its apparent economic necessity in the mid-nineteenth century. The whole moral case aside, Melville makes several references to harpooners, including:

Drink ye harpooners! drink and swear, ye men that man the deathful whaleboat’s bow.

To insure the greatest efficiency in the dart, the harpooners of this world must start to their feet from out of idleness, and not from out of toil

And then there was the 2021 mini-series North Water https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_North_Water_(TV_series) in which Colin Farrell played harpooner and thug Henry Drax. North Water was a fictionalised account of a ship named Volunteer, a whaler sailing from Hull in 1859. The story is fiction, but I believe that a lot of the detail of nineteenth century Hull, life and relationships on-board, and the inhospitable lands to which they sailed is undoubtedly true to life. The story I want to tell is of a real ship named the Chase that sailed from Hull that same year. The principal source for this story is an article that appeared in the Hull Packet on 4 November.

Chase, 1859

| Author’s notes on the text that follows: 1. where surnames are capitalised it indicates a link to my family tree 2. whales were always referred to as ‘fish’ 3. fish were measured by the size of their jaw bone – the whale itself would typically have been four or five times the length indicated 4. a ‘line’ was 120 fathoms (220 metres) in length, so the fish that took out ten lines mentioned below required over 2km of rope. |

Departure from Hull

At half past four on the afternoon of Tuesday 15 February 1859, by 2 x great grandfather William CLARK and his brother George left the Humber Dock on the screw-steamer Chase, under the command of Captain John Gravill. John Gravill would have been a proud man that afternoon because the other vessel leaving the safety of the Dock for the frozen north was the Diana, captained by his son, John Gravill junior. The papers reported a large crowd cheering lustily as the vessels left the pier.

William was thirty-nine years old (the same age as Queen Victoria, whom he would go on to outlive by just one year). His brother George, nine years his junior, was already showing himself to be the more assiduous of the two (he would go on to obtain a chief mate’s certificate – the second in command).

The voyage began inauspiciously. The Chase lost an anchor in Grimsby Roads, no more than fifteen miles out of Hull. However, five days later the Chase arrived at Lerwick in the Shetlands, five hundred miles from home. Over the following two weeks she completed her complement of crew from amongst the Shetland men. Setting sail again on Wednesday, 2 March.

Sealing grounds near Jan Mayen Island

They reached the ice on the eleventh and saw seals on the nineteenth and, again on twenty first by which time they were in sight of Jan Mayen Island, eight hundred miles north of Lerwick. By 29 March they had crossed the Arctic Circle and reached latitude 70 degrees and 34 minutes: longitude 10 degrees and 12 minutes west. By Friday, 1 April the ice was very heavy, nipping the ship front and back, carrying away the rudder. A new rudder was fitted and all waited for the ice to break up and offer some passageway through. Two weeks passed. On the sixteenth, with no sign of any break in the ice, a dock was cut, but all the men’s efforts were in vain when the pressure of the ice meant that the dock simply closed up.

The Chase was now just inside the Arctic Circle at latitude 67 degrees and 44 minutes: longitude 15 degrees and 35 minutes west. The thickening ice lifted the ship several feet out of the water and penetrated the hull requiring the crew to use both pumps every half hour. Boats, provisions and clothes were unloaded onto the ice.

With no material improvement in conditions, on Monday, 2 May an attempt was made to blow up the ice, but it refused to release its grip. Three of four days’ effort was given again to attempting to saw through the ice to create a passage, but again to no avail. Finally, on Sunday, 8 May the swell forced the ice to release the Chase, and by the twelfth the ship was on the way back to Lerwick, shipping a small, but manageable amount of water. The sealing had been unsuccessful, but at least the ship and the men had survived.

Setting sail for the whaling grounds

On 17 May the Chase made Lerwick, where she was immediately grounded in order to exchange her battered screw and to allow other repairs to be made. Ten days later the Chase left Lerwick headed for Davis’ Straits. Icebergs were first seen two weeks later on Saturday, 11 June. Two days later the Chase was twenty five miles northwest of Queen Ann’s Cape and two days later passed Disco Island. The first whale was sighted the following day. The Chase sailed on past Brown’s Island and the Duck Islands on 18 June and then to Melville Bay in an attempt to find a passage northward. Again the ice thickened, but the sky suggested there was open water ahead if they could only find a way through. However, Gravill and his men could not find a way through, and on Sunday 19 June the Chase was again beset by ice. John Gravill was a devoutly religious man, forbidding his men to hunt, and often to work, on the Sabbath. But this time, even though it was a Sunday, an attempt was made to recover the rudder before it could be damaged. Unfortunately the ice was too quick, and, closing suddenly around them, it carried away the main piece and tore part of the stern.

Once again destruction seemed inevitable. The sternpost cracked under the strain; the quarterdeck was raised two inches out of position; the fan shaft strained and the Chase was shipping a great quantity of water. Food and clothes were again removed and stored on the ice whilst the men waited for the inevitable. However, the currents changed and the ice began to break up and by dodging the thick pack ice the Chase was able to find a passage northward, such that on Wednesday 29 June, Cape York was twenty five miles north east by north. More bad fortune ensued when the Chase collided with the Diana captained of course by his son, staving two of her boats and causing other injuries.

On 30 June they passed Cape York and, on 2 July, Cape Byam Martin. All sails were set and the Chase made all haste for Lancaster Sound with the inshore ice frozen into one continuous floe. Whales were again sighted on Sunday, 3 July, but as it was the Sabbath none were caught. On the fourth a whale rose close by, but again got away. William CLARK was first to make a catch when on seventh using the new Balchin bomb lance he shot a small whale of about twenty-five feet in length.

Friday 8 July was a busy day. All the boats were out Richard BYERS shot a killed a larger fish (bone 7ft 2in). George CLARK shot another, but the lines broke. He immediately hit another but after an hour or so the harpoon came loose. William was on target with a long shot, but again the harpoon dislodged. Joseph Keld shot at a fifth but the gun was not loaded properly and the fish was spared. On their return to the ship the men were rewarded with all hands being ordered to the pumps, for the Chase was still shipping a considerable amount of water.

After a short rest the men were back in pursuit. William shot a fish that took out ten lines, but after two hours the harpoon broke. Henry Smith shot a second small fish (3ft 8in) at nine and it was alongside by ten. George CLARK then attempted to fire at one beneath the water, but missed. At four o’clock Joseph Keld hit another fish, which took out nearly fifteen lines over seven hours, before again giving them the slip. George CLARK was then successful in killing a 6ft 9in fish that was finally alongside at midnight. The log records, ‘Dundee harpoon in her; foreganger broken or cut’. The following day a large number of fish were seen, but it was the Sabbath and so no boats were put out. On Monday, 11 July the hunting continued. The ship was moored to the floe and all boats sent away in pursuit. William CLARK again had the first shot, but missed. William Denton then fired at two further fish, but again unsuccessfully. His third attempt was more fortuitous, securing a 9ft 5in fish in around ninety minutes. John Smith shot a fifth, but it got away after taking our five lines. Richard Byers then shot a sixth fish (10ft), which died within an hour. All this before noon. However, in the afternoon all had to return to Chase to man the pumps as she was still taking on water at an alarming rate.

The following day there was more success. Eight boats were out and Henry Smith (9ft), George CLARK (4ft 1in), Joseph Keld (4ft 2in) and William CLARK (8ft 3in) were all successful. Richard BYERS lost one when the harpoon broke. The following day, Wednesday 13 July, the men rested and flensed the fish they’d caught the previous day. On 14 July 1the pumps were in constant use. The fifteenth saw William CLARK and Joseph Keld shoot at two fish but both were lost. For two days Chase was now again beset by ice, but on 19 July she managed to get into Pond’s Bay, sighting another fish as she did so. Cape Hay was seen on Friday, 22 July. There was little ice in Lancaster Sound and so Chase steamed south for Pond’s Bay. On Monday, 1 August William CLARK shot a large fish (10ft 4in) which took out over twelve lines. The Jumma also struck the same fish and then lowered all her boats to claim the fish. Captain Gravill proposed dividing the fish even though William CLARK had made the first shot. The captain of the Alexander which was in company at the time confirmed this too. The mate and crew of the Jumma however would not agree to this and took the fish.

Occasional fish were sighted, but on Wednesday, 10 August they again appeared in number and William CLARK killed one (9ft 7in) and William Denton shot another large fish (9ft 2in) at midnight which was cut up the next day. Henry Smith shot another large fish (10ft), which required five boats to tow it back to the Chase. William CLARK hit another on the twelfth, but the harpoon again broke. On the thirteenth several fish were seen but none were killed. On the fifteenth Joseph Keld shot another (10ft). On the same day seven men came aboard from the Advice which had been crushed with the loss of the ship and a full cargo of oil . On 18 August the Chase was again beset by ice and nipped so that once again the boats were unloaded onto the ice, but peril passed once again. On Tuesday 30 August George CLARK shot and killed another fish (9ft 6in). On Monday, 5 September one of the Advice’s men who was aboard another ship Abram died and was buried. On Thursday, 8 September the Chase passed Cape Broughton on her way home but encountered very heavy weather. By Tuesday, 11 October though she was plying into St Magneus Bay; steaming out of harbour and passing Fitful-head on Monday the seventeenth. A pilot came on board at Spurn Head on Friday, 21 October and the ship was moored back at Humber Dock after one of the most perilous voyages that has been recorded for some years, but which by gallantry, perseverance and good seamanship has been brought to a successful termination. The cargo of the Chase summed up to a total of 125 tons of oil and 7 tons of bone.

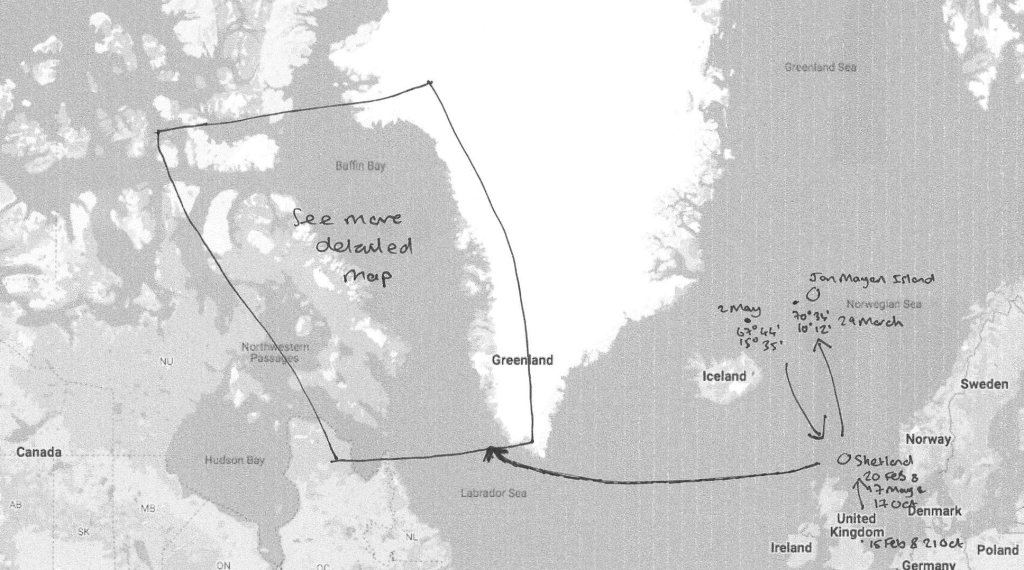

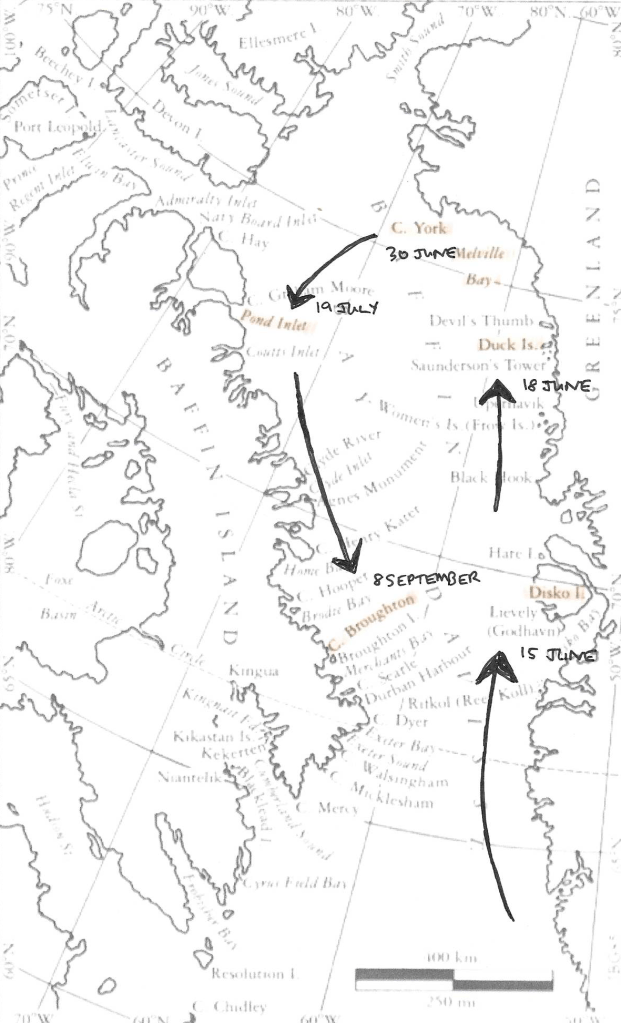

Maps of the voyage

A legal case surrounding the disputed fish

Almost exactly eighteen months after the event a legal case came before the Scottish Court of Sessions – Second Division, with the owners of Chase seeking to recover £1,005 from the Tay Whale Fishing Company, the owners of Jumma. Evidence was heard over two days with the incident being reported as follows:

At about 6 o’clock at night, on 1st of August [1859], the captain of the Chase saw two whales and immediately sent eight boats in pursuit. One of the boats shot a harpoon into one of the whales, which took out 11 lines of 120 fathoms each. The crew threw up an oar in signal of their success, and the Chase hoisted her jack to announce to their boats the circumstance. The whale played about for a considerable time, and, in the meantime, some boats of the Jumma were lowered and some of her crew were sent across to lance the fish and make it leave a hole into which it had got. The whale rose near to the Jumma’s boats, when the crew shot three harpoons into her, and after a while the whale was finally killed, when the Jumma’s crew claimed and took possession of it.

On the third day of the legal proceedings the parties agreed to settle with the owners of Chase receiving £200 and both sides agreeing to meet their own costs.

A lucrative voyage?

Whaling was a very uncertain trade. Whilst they were at the whaling grounds their wives would be able to draw a monthly ‘Allotment’. I have examples of £1 per month from the 1850s and £2 per month from the 1870s. All the men would be paid a small daily amount plus a share based on the oil and bone brought back. Harpooners would also get ‘strike money’ baseThere could also be deductions for tobacco, supplies, slops and insurance. If a ship came back clean – i.e. without having caught any fish – as a proportion often did, the men might end up owing money after the voyage.

A lot was down to the skill of the captain, and the ability of the crew to work together. If the captain changed ship, many crew members would follow him to the new ship. I believe my 2 x great grandfather sailed with John Gravill for over twenty years. 1859 was a perilous voyage, but also successful

From analysis of the records I have I believe that my 2 x great grandfather would have earned a £12 basic wage for 8 months work; around £2 strike money; around £50 for his share of the oil money and around £9 for his share of the bone money, so around £73 in total. How much is this equivalent to today? There are lots of ways of measuring this (and I’ll write a post about this at some point), but my preference is to use http://www.measuringworth.com and a ‘relative income’ method of comparison. This measure effectively allows for three things: prices have increased; wages have increased more; there is more stuff we need to buy now in order to feel as well off. Effectively I’m answering the question, ‘How much might you need to earn today in order to feel as well off now as William would have done in 1859?’ On this basis £73 is equivalent to around just under £80,000. So a very good year. But notice that over 80% of this amount is performance related: if the ship had come back ‘clean’ his earnings would have been equivalent to around just £13,000.

Postscript

Using these same conversion terms the present day value of the whale disputed with the Jumma was about £1.1 million, whilst the £1 and £2 Allotments paid to wives were equivalent to about £1,000 and £1,500 a month respectively.

A stylised picture of the Chase and Diana can be found here https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Diana_and_Chase_in_the_Arctic.jpg. A number of Hull artists specialised in producing these sort of paintings for owners. The picture ‘poetically’ illustrates all the activities as happening in one place and time.

Bibliography

- Melville, Herman. 2008. Moby Dick. Oxford: Oxford World Classics

- Hull Packet, 4 November 1859, 5

- Hull Packet 21 October, 1859, 5c

- Dundee Advertiser, 1 February 1861

- Greenock Advertiser, 2 February 1861

Leave a comment